Nice NYT piece on the legendary PKD. One of my favourite SF authors. We all have a different favourite title - mine has long been A Scanner Darkly (the movie was OK, but the book is quite definitely better), but the wonderful distillation of is ideas on Eye in the Sky is suberb too. 'Even' his theologically inclined works are a treat, as the territory they explore is as much about inner space nd subjective interpretation as it is about any 'deity', and, anyway, is theologically light-years above the dumbed down congregationalist brainwashing fodder most flocks are peddled. So, whether one agrees or disagrees with PKD's point (and he is not consitent on detail, though he gets more so with the fundamentals as he goes along), there are amazingly fertile philosophical riffs for the reader to explore in a feedback with the text.

Now that the noirish special-effects brigade have been mining the early short-stories, many set in a late fifties paranoid 'men-in-black' McCarthyite influenced future world, and a long needed advance into his more mature territories has been assailed (in Linklater's A Scanner Darkly), perhaps some deeper and less showy explorations of his ideas may find their way onto 'celluloid'.

Linklater's Waking Life is an indication that his version of Scanner is the tip of the iceberg for that director alone. Others? Well, Tarkovsky is gone, perhaps Lars von Trier might have a go at Ubik and Valis...? Any ideas?

- Tim

A Prince of Pulp, Legit at Last

By CHARLES McGRATH

ALL his life the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick yearned for what he called the mainstream. He wanted to be a serious literary writer, not a sci-fi hack whose audience consisted, he once said, of “trolls and wackos.” But Mr. Dick, who popped as many as 1,000 amphetamine pills a week, was also more than a little paranoid. In the early ’70s, when he had finally achieved some standing among academic critics and literary theorists — most notably the Polish writer Stanislaw Lem — he narced on them all, writing a letter to the F.B.I. in which he claimed they were K.G.B. agents trying to take over American science fiction.

ALL his life the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick yearned for what he called the mainstream. He wanted to be a serious literary writer, not a sci-fi hack whose audience consisted, he once said, of “trolls and wackos.” But Mr. Dick, who popped as many as 1,000 amphetamine pills a week, was also more than a little paranoid. In the early ’70s, when he had finally achieved some standing among academic critics and literary theorists — most notably the Polish writer Stanislaw Lem — he narced on them all, writing a letter to the F.B.I. in which he claimed they were K.G.B. agents trying to take over American science fiction.So it’s hard to know what Mr. Dick, who died in 1982 at the age of 53, would have made of the fact that this month he has arrived at the pinnacle of literary respectability. Four of his novels from the 1960s — “The Man in the High Castle,” “The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch,” “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” and “Ubik” — are being reissued by the Library of America in that now-classic Hall of Fame format: full cloth binding, tasseled bookmark, acid-free, Bible-thin paper. He might be pleased, or he might demand to know why his 40-odd other books weren’t so honored. And what about the “Exegesis,” an 8,000-page journal that derived a sort of Gnostic theology from a series of religious visions he experienced during a couple of months in 1974? A wary, hard-core Dickian might argue that the Library of America volume is just a diversion, an attempt to turn a deeply subversive writer into another canonical brand name.

Another thing that would probably amuse and annoy Mr. Dick in about equal measure are the exceptional number of movies that have been made from his work, starting with “Blade Runner” (adapted from “Do Androids Dream”), 25 years old this year and available in the fall on a special “final cut” DVD. The newest, “Next,” taken from a short story, “The Golden Man,” starring Nicolas Cage as a magician able to see into the future and Julianne Moore as an F.B.I. agent eager to enlist his help, opened just last month. In the works is a biopic starring Paul Giamatti, who bears more than a passing physical resemblance to the author, who by the end of his life had the doughy look of a guy who didn’t spend a lot of time in the daylight.

Mr. Dick died while “Blade Runner” was still in production, already unhappy about the shape the script was taking, though not the kind of money he hoped to realize. “Blade Runner” is probably the best of the Dick movies, if not the most faithful. (That honor probably belongs to “A Scanner Darkly,” released last year, in which Richard Linklater’s semi-animated technique suggests some of the feel of a graphic novel.)

There’s no reason to think Mr. Dick would have approved any more of the others, especially “Total Recall,” in which Quail, the nerdish hero of Mr. Dick’s story “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale,” turns into Quaid, a buffed-up Arnold Schwarzenegger character. Meanwhile, as several critics have noted, movies like the “Matrix” series, “The Truman Show” and “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,” though not based on Dick material, still seem to contain his spark, and dramatize more vividly than some of the official Dick projects his essential notion that reality is just a construct or, as he liked to say, a forgery. It’s as if his imaginative DNA had spread like a virus.

Part of why Mr. Dick’s work appeals so much to moviemakers is his pulpish sensibility. He grew up in California reading magazines like Startling Stories, Thrilling Wonder Stories and Fantastic Universe, and then, after dropping out of the University of California, Berkeley, began writing for them, often in manic 20-hour sessions fueled by booze and speed. He could type 120 words a minute, and told his third wife (third of five, and there were countless girlfriends: Mr. Dick loved women but was hell to live with), “The words come out of my hands, not my brain, I write with my hands.”

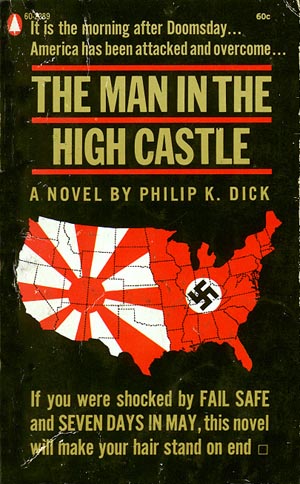

His early novels, written in two weeks or less, were published in double-decker Ace paperbacks that included two books in one, with a lurid cover for each. “If the Holy Bible was printed as an Ace Double,” an editor once remarked, “it would be cut down to two 20,000-word halves with the Old Testament retitled as ‘Master of Chaos’ and the New Testament as ‘The Thing With Three Souls.’ ”

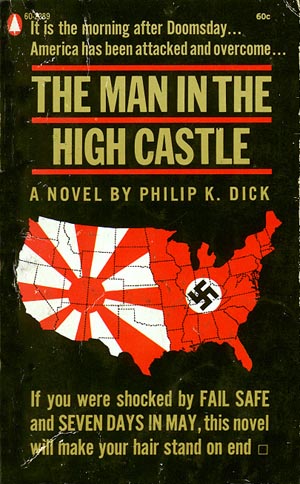

So for the most part you don’t read Mr. Dick for his prose. (The main exception is “The Man in the High Castle,” his most sustained and most assured attempt at mainstream respectability, and it’s barely a sci-fi book at all but, rather, what we would now call a “counterfactual”; its premise is that the Allies lost World War II and the United States is ruled by the Japanese in the west and the Nazis in the east.) Nor do you read him for the science, the way you do, say, Isaac Asimov or Robert Heinlein.

Mr. Dick was relatively uninterested in the futuristic, predictive side of science fiction and embraced the genre simply because it gave him liberty to turn his imagination loose. Except for the odd hovercar or rocket ship, there aren’t many gizmos in his fiction, and many of his details are satiric, like the household appliances in “Ubik” that demand to be fed with coins all the time, or put-ons, like the bizarre clownwear that is apparently standard office garb in the same book (which is set in 1992, by the way; so much for Dick the prophet): “natty birch-bark pantaloons, hemp-rope belt, peekaboo see-through top, and train engineer’s tall hat.”

To a considerable extent Mr. Dick’s future is a lot like our present, except a little grungier. Everything is always running down or turning into what one of the characters in “Do Androids Dream” calls “kipple”: junk like match folders and gum wrappers that doubles itself overnight and fills abandoned apartments. This sense of entropy and decline is what Ridley Scott evokes so well in “Blade Runner,” with its seedy, rainy streetscapes, and what Steven Spielberg misses in his slightly schizoid “Minority Report,” in which Tom Cruise waves his hands at that glass console, as if it were a room-size Wii system.

The theme of “Minority Report” — pre-cognition, or the idea that certain people, “precogs,” can foresee the future, with not always happy results — was an idea that Mr. Dick began exploring in the mid-’50s, along with themes of altered or repressed memory, which became the subject of “Total Recall,” “Impostor” and, more recently, John Woo’s “Paycheck.” Most of the Dick-inspired movies come from short stories of this period — several of them, including “The Golden Man,” written in the space of just a few months.

In the ’60s Mr. Dick turned his energies to novel writing, and with the exception of “Do Androids Dream” (considerably dumbed down in “Blade Runner”) and “A Scanner Darkly” (published in 1977 and, incidentally, the first book Dick wrote without the assistance of drugs) the novels don’t lend themselves so readily to the Hollywood imagination.

In the ’60s Mr. Dick turned his energies to novel writing, and with the exception of “Do Androids Dream” (considerably dumbed down in “Blade Runner”) and “A Scanner Darkly” (published in 1977 and, incidentally, the first book Dick wrote without the assistance of drugs) the novels don’t lend themselves so readily to the Hollywood imagination.That’s because they’re much harder to reduce to a single concept or plot line. Three of the novels collected in the Library of America volume — “Do Androids Dream,” “The Three Stigmata” and “Ubik — are arguably Mr. Dick’s best. (Some diehards hold out for “VALIS,” his last major work, but that’s really his “Finnegans Wake” — a book more fun to talk about than to read.) All three are less gimmicky than the stories and are preoccupied with two big questions that became his obsession: How do we know what is real, and how do we know what is human? For all I know, you could be a robot, or maybe I am, merely preprogrammed to think of myself as a person, and this thing we call reality might be just a collective hallucination.

This kind of speculation — the stuff of so many hazy, bong-fed dorm-room bull sessions — takes on genuine interest in Mr. Dick’s writing because he means it and because he invests the outcome with longing. His characters, like Rick Deckard, the android-chasing bounty hunter in “Do Androids Dream,” desperately want something authentic to believe in, and the books suggest that the quality of belief may be more important than the degree of authenticity.

“The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch” and “Ubik,” written five years apart, are in many ways two versions of the same story, one tragic and one mostly comic. The title character of “The Three Stigmata” (1964) is not much to look at — his stigmata are steel teeth, a robotic arm and replacement eyes — but he still possesses Godlike, or perhaps Satanic, powers, and is able, with the help of a drug called Chew-Z, to enmesh people in webs of hallucination, one within another, so slippery and perplexing that even the reader feels a little discombobulated. The book is a horror story of the imagination gone amok.

“Ubik” (1969) is more redemptive. The godlike figure here is an entrepreneur named Glen Runciter, who runs what’s called a “prudence organization”: for a fee, he will debug your company and rid it of “teeps,” or secret-stealing telepaths. He manages to communicate with some of his former employees even when they’re dead and supplies them with a salvific aerosol spray, called Ubik, that appears to at least temporarily resist the tendency of everything to regress backwards to the way it was in 1939. Mr. Dick describes Depression-era artifacts — Philco radios, Curtis Wright biplanes — with great affection, however, and in this book death turns out not to be so bad; it isn’t eternal extinction, but a kind of half-life partly imagined by a restless young man (also dead) named Jory.

Jory is a bit of menace, but Mr. Dick has a soft spot for him as a dreamer and fantasist, as he does in “The Three Stigmata” for the colonists on Mars who, bored silly, like to get stoned and play with their Perky Pat layouts, elaborate Ken and Barbie sets that let them make up nostalgic stories about life on Earth. He also likes to embed in his books still other books, emblems of imaginative possibility, like the novel in “The Man in the High Castle” that postulates an Allied victory.

Jory is a bit of menace, but Mr. Dick has a soft spot for him as a dreamer and fantasist, as he does in “The Three Stigmata” for the colonists on Mars who, bored silly, like to get stoned and play with their Perky Pat layouts, elaborate Ken and Barbie sets that let them make up nostalgic stories about life on Earth. He also likes to embed in his books still other books, emblems of imaginative possibility, like the novel in “The Man in the High Castle” that postulates an Allied victory. There is doubtless an autobiographical element to Mr. Dick’s novels; they read like the work of someone who knows from experience what it’s like to hallucinate. Lawrence Sutin, who has written the definitive biography of Mr. Dick, says that he took LSD only a couple of times, and didn’t particularly like it. On the other hand his regular regimen of uppers and downers, gobbled by the handful, was surely sufficient to play tricks with his head, and Mr. Dick worried more than once that he might be turning schizophrenic.

The books aren’t just trippy, though. The best of them are visionary or surreal in a way that American literature, so rooted in reality and observation, seldom is. Critics have often compared Mr. Dick to Borges, Kafka, Calvino. To come up with an American analogue you have to think of someone like Emerson, but nobody would ever dream of looking to him for movie ideas. Emerson was all brain, no pulp.

ALL his life the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick yearned for what he called the mainstream. He wanted to be a serious literary writer, not a sci-fi hack whose audience consisted, he once said, of “trolls and wackos.” But Mr. Dick, who popped as many as 1,000 amphetamine pills a week, was also more than a little paranoid. In the early ’70s, when he had finally achieved some standing among academic critics and literary theorists — most notably the Polish writer Stanislaw Lem — he narced on them all, writing a letter to the F.B.I. in which he claimed they were K.G.B. agents trying to take over American science fiction.

ALL his life the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick yearned for what he called the mainstream. He wanted to be a serious literary writer, not a sci-fi hack whose audience consisted, he once said, of “trolls and wackos.” But Mr. Dick, who popped as many as 1,000 amphetamine pills a week, was also more than a little paranoid. In the early ’70s, when he had finally achieved some standing among academic critics and literary theorists — most notably the Polish writer Stanislaw Lem — he narced on them all, writing a letter to the F.B.I. in which he claimed they were K.G.B. agents trying to take over American science fiction. Part of why Mr. Dick’s work appeals so much to moviemakers is his pulpish sensibility. He grew up in California reading magazines like Startling Stories, Thrilling Wonder Stories and Fantastic Universe, and then, after dropping out of the University of California, Berkeley, began writing for them, often in manic 20-hour sessions fueled by booze and speed. He could type 120 words a minute, and told his third wife (third of five, and there were countless girlfriends: Mr. Dick loved women but was hell to live with), “The words come out of my hands, not my brain, I write with my hands.”

Part of why Mr. Dick’s work appeals so much to moviemakers is his pulpish sensibility. He grew up in California reading magazines like Startling Stories, Thrilling Wonder Stories and Fantastic Universe, and then, after dropping out of the University of California, Berkeley, began writing for them, often in manic 20-hour sessions fueled by booze and speed. He could type 120 words a minute, and told his third wife (third of five, and there were countless girlfriends: Mr. Dick loved women but was hell to live with), “The words come out of my hands, not my brain, I write with my hands.”  In the ’60s Mr. Dick turned his energies to novel writing, and with the exception of “Do Androids Dream” (considerably dumbed down in “Blade Runner”) and “A Scanner Darkly” (published in 1977 and, incidentally, the first book Dick wrote without the assistance of drugs) the novels don’t lend themselves so readily to the Hollywood imagination.

In the ’60s Mr. Dick turned his energies to novel writing, and with the exception of “Do Androids Dream” (considerably dumbed down in “Blade Runner”) and “A Scanner Darkly” (published in 1977 and, incidentally, the first book Dick wrote without the assistance of drugs) the novels don’t lend themselves so readily to the Hollywood imagination. Jory is a bit of menace, but Mr. Dick has a soft spot for him as a dreamer and fantasist, as he does in “The Three Stigmata” for the colonists on Mars who, bored silly, like to get stoned and play with their Perky Pat layouts, elaborate Ken and Barbie sets that let them make up nostalgic stories about life on Earth. He also likes to embed in his books still other books, emblems of imaginative possibility, like the novel in “The Man in the High Castle” that postulates an Allied victory.

Jory is a bit of menace, but Mr. Dick has a soft spot for him as a dreamer and fantasist, as he does in “The Three Stigmata” for the colonists on Mars who, bored silly, like to get stoned and play with their Perky Pat layouts, elaborate Ken and Barbie sets that let them make up nostalgic stories about life on Earth. He also likes to embed in his books still other books, emblems of imaginative possibility, like the novel in “The Man in the High Castle” that postulates an Allied victory.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home